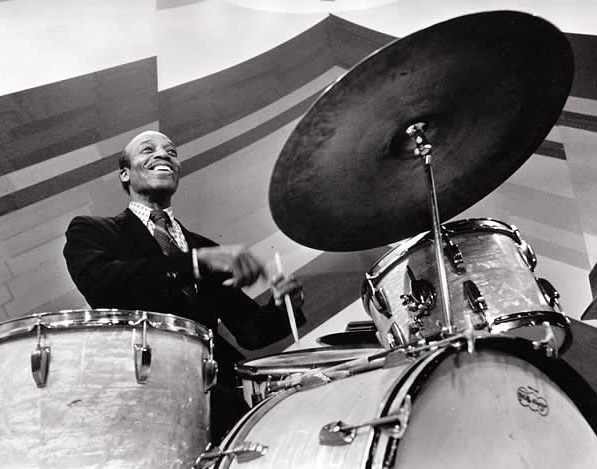

KRUPA PLAYS MULLIGAN NOW ON CD FROM VERVE

Tuesday, May 10th, 2005There’s no rhyme or reason to Verve Records’ reissue program, especially when it comes to Gene Krupa. It often seems, in fact, that Gene really gets the short end of the stick (pardon the pun) when it comes to putting out vintage product on CD. As an example, the famed “Big Noise From Winnetka” CD is available only as an import, as are the “Sextet Sessions” compilations. Basically, only “Krupa and Rich” and the “Original Drum Battle” are commonly available, and none of these projects have any unissued or alternate takes, and no one even bothered to write a set of updated linear notes. Many of us remember when the “Original Drum Battle” was released on CD, and we had all hoped for a bunch of additional, unissued material. Other than restoring Ella Fitzgerald’s vocal on “Perdido,” there was nothing else new.

“Gene Krupa Plays Gerry Mulligan Arrangements” is no exception. Recorded in 1958 with an all-star group that included Phil Woods, Hank Jones, Kai Winding, Urbie Green and many more, the recording received four stars from Down Beat magazine when it was reviewed in 1959. It was and it is superb, albeit not particularly inspiring. Mulligan’s charts, most written in 1946, held up when this was recorded and for the most part still hold up today. Though a couple of the songs could have used another take or so, it is generally well done. Gene is not really featured on this date, other than for a few breaks here and there, and you can hear that he’s really devoted to playing Mulligan’s charts properly. The charts are the star on this recording, and as a matter of fact, Mulligan actually conducted four of the twelve tunes on this outing. The other “star,” if there was one, was alto saxophonist Phil Woods’ playing. Every Woods’ solo is an absolute gem. The stereo sound, by the way, is fabulous, and you can really hear everything that was going on.

What is terribly disappointing, though, is the lack of out takes, alternate takes, updated notes or any “extras” that we’ve come to expect from CD reissues. Although most of the Krupa discographers only list the master takes to this session, there simply had to be others during the course of these two recording dates. It is unlikely that every thing else, other than the masters, was destroyed. Most of the other artists who are the subject of Verve reissues, including Tal Farlow, Count Basie and many others, get the “full treatment.” Why not Gene? It makes one wonder why they put this thing out at all.

“Gene Krupa Plays Gerry Mulligan Arrangements,” in terms of sound, is a 96KHG, 24-bit digital transfer. I’m not sure what that means, other than to report to you that the sound is great. Verve Records, now owned by an outfit called the Universal Music Company, informs that this CD will only be available until March, 2008. Presumably, that makes it a “limited edition,” which is another thing I can’t figure out.

If any of our good supporters out there are having a problem finding this, let us know and I’ll make sure you get a copy. You should have it. I only wish there were more of it.

Keep swingin’

Bruce Klauber