FRANCES KLAUBER: From Gene and Buddy to Frank and Dean to Moe and Larry

Tuesday, July 26th, 2005Some may deem this to be a bit inappropriate, but it’s my web site and I can say and do what I want! And if that sounds like shades of “it’s my ball, so it’s my game,” so be it. Seriously, and forgive me if I’m a little sentimental at this time, so many of you–from all over the world–seem like family to me. I’ve never felt like anyone who ever visited JazzLegends.com was a “customer.” A supporter? Yes. A friend? Yes. Perhaps it’s because we all have one thing in common, no matter where we live and what our backgrounds may be. That’s the love of jazz, generally, and the music of Gene Krupa, to be more specific.

Those of you who have been receiving periodic, personal updates from me are aware that my mother, Frances, has pancreatic cancer. She just celebrated her 92nd birthday last month and she is as feisty as ever, but what she has just cannot be stopped and we’re told that time is relatively short. She is quite, quite comfortable in a convalescent home outside of Philadelphia, though she detests the food and is less than thrilled with the rotten chord changes of the pianist who comes into the dining hall to entertain a few times a week.

Frances knows changes and she knows tempos. She grew up in the vaudeville era, and from what I’ve been told, was an active participant in it as a singer and dancer in amateur shows all over the Philadelphia area. Indeed, the story goes that one or both of her brothers, Mitchell and Jack, used to go with her to gigs for the sole purpose of collecting the money thrown at Frances on the stage! The “take,” I’m told, could really add up for those days. I also understand from various sources through the years that my mother was asked to go on the road by some rather well-known vaudevillians. However, given the reputation of show business folk at the time (they were, of course, all drug addicts and drunks), Frances’ family absolutely and unequivocally forbid it. She could have made it. Her test recording of “Apple Blossom Time” came about seven years before The Andrews Sisters had the hit on it. Coincidentally, and we all know show business is bizzare, I went throught the same thing in 1978 with my recording of “Just a Gigolo” (David Lee Roth eventually had the hit on that one). Mom was the few who understood.

The business, though, was always in her blood. She played piano, by ear and in the key of G, at home constantly, and at family gatherings, she always entertained, many times with her brothers. She pushed me into taking music lessons at the age of six, first on accordion and later on flute. I hated both instruments, although I love them today. It wasn’t until my older brother, Joel (who many of you know as the renowned musicologist who studied with the legendary writer, Martin Williams), joined a band that I found the instrument I wanted to play. Joel was kind enough to bring me to one of the bands’ rehearsals, and in the corner of the room, there they were: a gold sparkle set of “Revere” drums (for the collectors out there, I believe Revere may have been an offshoot of “Kent”). I was hooked, and as most of you know, I still am.

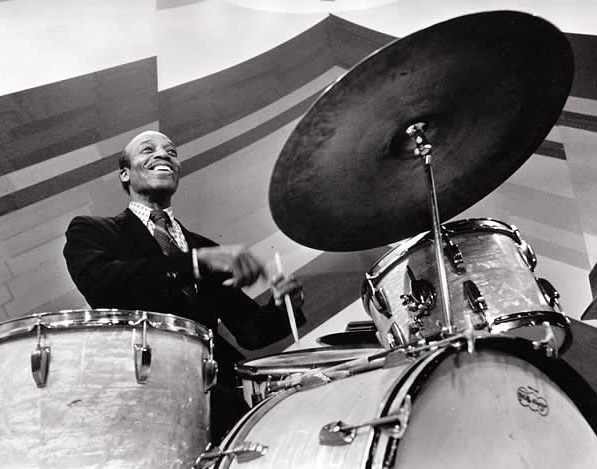

Like a lot of youngsters in the early 1960s, I wanted to take drum lessons. Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich were getting much television exposure, Joe Morello was the hippest guy out there, Art Blakey and the whole hard bop movement was helping to change the course of jazz, Maynard Ferguson’s band was swinging down the house, Sonny Payne was doing his stick-flipping bit with Basie, Cozy Cole was on the road as a result of his freak hit of “Topsy Part Two,” and even a guy named Sandy Nelson was hitting the pop charts with something called “Let There Be Drums.” My mother found me a good drum teacher, and I studied. And studied. There were a lot of teachers. And a lot of drums in our house.

Frances, who never drove an automobile, somehow managed to attend every performance of mine throughout the years — and there were many of them — at Cynwyd Elementary School, Bala-Cynwyd Junior High School, and Lower Merion High School. Over the years, and I know this was at Frances’ insistence, my brother and I where schlepped along at famed Philadelphia venues like The Latin Casino, The Celebrity Room and just about every place in the Catskill Mountains that featured live entertainment. Just as a sampling, we saw–more than once–Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis, Dean Martin, Shecky Greene and Bobby Darin, to say nothing of the jazz greats our father took us to see, including Harry James with Buddy Rich, Thelonious Monk, Sonny Stitt, Erskine Hawkins, Shirley Scott, Basie, Duke, Maynard, Lockjaw Davis, Woody, Duke, and of course, Gene Krupa. You would have had to have been there. There will never be another time like it, and I believe that if it were not for my mother, not only would I have never seen these legends, but I would not be doing what I’m doing or be who I am. When Gene was on the Mike Douglas Show in Philly, my mother made sure I was there.

Charlie Ventura called my mother at home one afternoon to ask for her permission: Could I sub for drummer Tony DeNicola for a few nights at The Saxony East club in Philadelphia? I was about 16. Not only did she give Charlie permission, but Frances organized a table of ten, front and center that very night, at The Saxony East to lend support. Charlie thanked her, in fluent Yiddish, believe it or not, that night.

My mother was often overshadowed by my more flamboyant father, but in her day, she was the one who got the things done that had to be done. In 1959, a local, children’s television host by the name of Sally Starr announced on her program that The Three Stooges were coming to Philadelphia at a club called The Latin Casino, then located at 13th and Walnut Street in center city. Non-Stooges fans may not understand, but I had to be there. I cannot imagine how distasteful this must have been for Frances and Charlie (I recall my father saying that The Stooges were corny when he was a boy), but we got there, and I guess I’m among the chosen few who can, today, say that “I saw The Three Stooges.” My mother got me there.

We have had our differences over the years and still do, but at times like this, one begins editing out the negative stuff. And that’s a good thing. After all, how many kids can say that their mom got them in to see The Three Stooges. That’s love. And I won’t forget it. Here’s hoping she’ll be bitching about bad chord changes for some time to come.

In “other business,” there is, we believe, an astounding new discovery on its way to Jazzlegends.com. We have heard a song or two over the years from a Jazz at the Philharmonic concert from Hamburg, Germany, from 1956. Some of you have heard the JATP ensemble introduce Krupa’s solo on “Drum Boogie,” and one of the versions of Gene backing Dizzy Gillespie on “My Man.” We understand that the entire concert, if not more, is available, with Gene as the only drummer of the evening, backing everyone from Dizzy to Ella Fitzgerald. Watch this space!

My sincere thanks to all of you, my friends, for allowing me this forum. God bless and keep swingin…

Bruce Klauber