LUCKY TO BE ED…SHAUGHNESSY, THAT IS

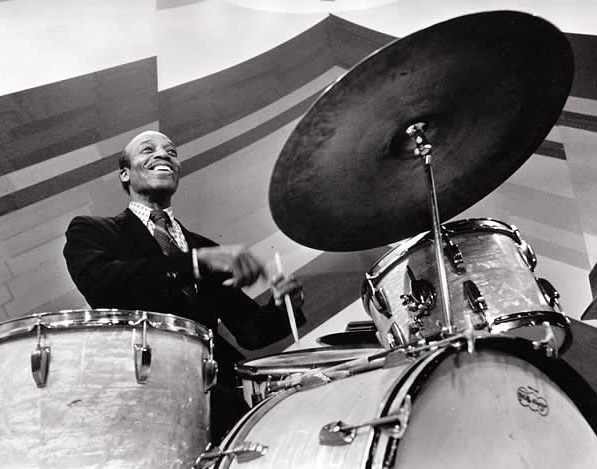

Monday, July 2nd, 2012Perhaps Gene Krupa, Buddy Rich and Ringo Starr were more famous, but no drummer in music history was more visible than Ed Shaughnessy. With rare exception, he appeared on network television five nights per week for an astounding 29 years, as the drummer in the big band led by Carl “Doc” Severinsen for “The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson.”

In his new autobiography, “Lucky Drummer: From NYC Jazz to Johnny Carson,” written with Robyn Flans, Shaugnessy tells of his decades with Doc, the jazz years that led up to that fabled gig, of the stars of jazz and jazz drumming with whom he’s worked, and of a personal life that, in some cases, just wasn’t easy.

The book, like its author, is a charmer. “Lucky Drummer” is touching, funny, informative and educational, honest though not brutally so, and at times heartbreaking. “Lucky Drummer” also serves as a guidebook for anyone who plays, or has wanted to play, drums professionally.

Though he claims he wasn’t really a percussion innovator or ground-breaker, the fact is, the pre-“Tonight Show” Shaughnessy backed some of the most progressive players in jazz. Those included vibist Teddy Charles, the larger-than-life bassist/composer Charles Mingus, tenor saxophonist-turned-Miles Davis-producer Teo Macero, odd time signature master Don Ellis, sitar player Ravi Shankar and tabla artist Alla Rakha, and the entire Marsalis Family.

On the more traditional end of the spectrum, the author played and recorded with Basie, Ellington, Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Wes Montgomery, George Benson, JImmy Smith, Quincy Jones, Billie Holiday and dozens of others. What a resume! The names on these lists, by the way, do not include the hundreds of players and singers he accompanied during his tenure on “The Tonight Show.”

Those in the the business, as well as the hundreds of students he’s taught and mentored, can attest that, along with his friend Louie Bellson, Ed Shaughnessy remains one of the nicest people out there, in any field.

Naturally, he shares plenty of stories about “the cats.” And he could have easily been negative about several of them, but as always, he’s taken the high road. His yarns about Anita O’Day, Buddy Rich, Benny Goodman, Jimi Hendrix, Mingus and Miles are often hilarious. The author could have been a lot more harsh when writing about how he was treated by a nasty Ray Charles. As is his wont, Shaughnessy goes relatively easy on “the genius.”

Especially gratifying is the space he gives to saxophonist/bandleader Charlie Ventura, Shaughnessy’s first “big name” employer. Ventura, almost forgotten now, was one of the biggest stars in jazz from the mid-1940s through the latter 1950s. This is the first book that deservedly addresses Ventura’s talents and contributions.

As of this writing, Ed Shaughnessy is 83 years old and is still out there playing, and playing very well. And after all these years, as he says, “The door is open, any time you see me and would like to talk. I’ve always been that way, and I will always be that way. I really love to talk with–and help, if I can–any younger musicians who come my way. I never forget that everybody did it for me.”

Due credit must be given Rob Cook of Rebeats for publishing an essential, must-read work.