Louis Prima, Jimmy Vincent and 9/11

Friday, September 11th, 2009Wherever and whenever live music is played—in Naples, Florida, or otherwise—people of a certain age will often request a song made famous by the late and great Louis Prima.

Last season in Naples at The Cafe’ on Fifth Avenue, when I had the privilege of playing with the great trumpter Bob Zottola, a customer approached me and requested that we do something by Louis.

Zottola, to his eternal and idealistic credit, is a music guy, not an entertainment guy, but wanted to honor the customer’s request.

Knowing I sang and played pretty much the complete Prima repertoire through the years—“if you want to make a dollar, you’ve got to make them holler,” has long been my credo–Bob asked me, “Is there anything like a tasteful Louis Prima song?”

“No, unfortunately, there isn’t,” I told Bob.

Louis was never a darling of the jazz critics.

We did “Oh Marie” anyway and the crowd loved it. Bob was really cooking on that one. It couldn’t be helped.

Prima’s sound was and is an electrifying, timeless and swinging one that transcended labels, genres, timelines or categories. In his early days, Louis was a good, traditionally oriented trumpeter and singer out of the Louis Armstrong mold, but as time went on, he moved farther and father away from jazz into the world of entertainment.

Indeed, via his group in Las Vegas that featured vocalist Keely Smith, to whom he was married from 1953 to 1961, he made one of the biggest splashes in entertainment history in the Vegas lounges, on records, and in clubs throughout the country. Along with the architect of the Prima sound –the recently-departed saxophonist Sam Butera—the Prima book combined elements of Dixieland jazz, early rhythm and blues, the Italian jive novelties he had been doing for years, plus the deadpan vocals of Keely, to fashion an eclectic and singular sound that has never been duplicated. Many have tried, included Sonny and Cher, who basically lifted the Louie and Keely act, updated it and tried to make it their own,

Prima continued, with varying degrees of success and with changes in music policy—he was almost doing a rock and roll show at one point in later years—until he lapsed into a coma in October of 1975. He died in August, 1978.

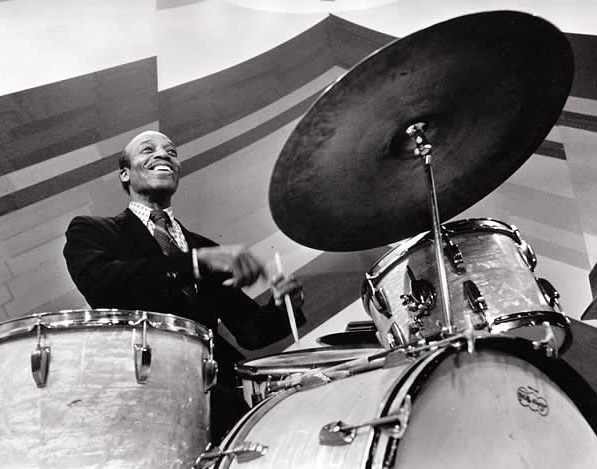

Prima’s drummer on and off since the early 1940s was a superb player by the name of Jimmy Vincent, who died on April 15, 2002.

You can hear Vincent wailing away on some of Louis’ most famous songs, including “Jump Jive and Wail,” “Just a Gigolo” and all of the rest.

Vincent also had a good deal of success with another, semi-famed, Las Vegas-based lounge group called “The Goofers.” Drum fans, in particular, may remember Vincent appearing in ads for the Slingerland Drum Company, where he was wearing a monkey mask.

Vincent never cared about critics. If you wear a monkey mask while playing the drums, that’s obvious. But Buddy Rich, among well-known players, is said to have loved him. No one could play the shuffle beat like Jimmy Vincent.

On the morning of September 11, 2001, singer Joy Adams and I were waiting for a cab to pick us up at our Philadelphia home to take us to the airport. We were flying to Las Vegas to get together with drummer Jimmy Vincent, who was to be interviewed and featured in a Hudson Music DVD, which then had the working title of “Roots of Roll Drumming.” Eventually, it was released as “Classic Rock Drum Solos,” but the idea was the same, which was to trace the evolution of the drum solo as it ultimately applied to rock and roll,

Vincent was an important figure in this area, having helped pioneer and perfect the shuffle beat on drums, an important component of early rock.

At about 10 a.m., a few minutes before our taxi was scheduled to arrive in Philadelphia, Joy’s daughter, Lauren, called us at home. “Turn on the television, now,” she told her mother.

“What channel?” Joy asked.

“Any channel,” Lauren said.

There it was. The tragic bombing of the Word Trade Centers. Live, on television.

We didn’t believe what we were seeing.

The taxi had arrived to take us to the airport. My first thought was to call the airport to see if planes were still flying. Whomever answered the phone at the airport said that nothing had changed, Planes were still taking off.

They didn’t for long.

The trip to Vegas never happened and we never hooked up with Jimmy Vincent, who passed away about a year and one-half later.

“Classic Rock Solos” features an early, 1940s drum solo by a 16-year-old player by the name of Jimmy Vincent, tearing it up on a song written by his long-time boss, Louis Prima. The song’s title was “Sing Sing Sing.”

Bob Zottola has spoken often about doing that number when I come back to Naples.

I plan on it.