On May 30, 2009, Benny Goodman, a.k.a. “The King of Swing,” would have been 100 years old. There were and are several Goodman tributes, including a BBC Radio “Centenary” episode, concerts by Paquito D’Rivera, the Boston Symphony and a Lincoln Center “Jazz for Young People” show entitled “Who is Benny Goodman?”

There are several players and leaders out there who do ensure that the Goodman legacy continues. Ken Peplowski (who will do a Goodman tribute concert at The Rochester Jazz Festival on June 13), Brooks Tegler, and especially Loren Schoenberg — who could and should write the definitive Benny Goodman story—are three who immediately come to mind. And Schoenberg, by the way, paid tribute to BG, and Lester Young, via several, recent WGBO radio programs. While all this is great stuff, it seems to me that there should be more, given the scope of Benny Goodman’s fame and more than substantial contributions. But memories fade as time goes on, so maybe we should be thankful for any tributes at all.

As much a part of the Goodman legend, if there is such a thing, is the not-so-fondly-remembered issue of his personality. Though I don’t like getting involved in the personal lives of any celebrity, the Goodman “personality,” or lack of it, is just so darn amusing and very, very public, that it just cannot be ignored. Especially on BG’s 100th.

One of Goodman’s biographers, perhaps James Lincoln Collier (and whatever happened to him?) once pointed out that, in all probability, not a day goes by without a story being told about the enigmatic behavior of BG. (Buddy Rich stories are another issue.) Gene Lees’ essential “Jazzletter” devoted a bunch of past issues to what went down on the famed tour of Russia in 1962, and Bill Crow’s “Jazz Anecdotes” retold some of the more infamous stories.

The one I particularly like is the one told in the late, Peter Levinson’s great biography of Tommy Dorsey, published in 2005, entitled “Tommy Dorsey: Livin’ in a Great Big Way.”

As the story goes, BG was doing a gig somewhere on November 27, 1956, the day after Dorsey died. One of Goodman’s sidemen told Benny the news about TD’s tragic and unexpected death. “Benny, I hate to tell you this bad news, “ the sideman related, “but Tommy Dorsey just died.” The King’s reply? “Is that so?” he said. You’ve got to love it.

Another frequently-told story through the years that has again been making the rounds of the internet, is pianist/vocalist Dave Frishberg’s hilarious tale of the evening Goodman sat in with Gene Krupa’s Quartet at The Metropole Cafe’ in New York city. Track that one down. It’s a riot.

I haven’t related my personal Benny Goodman story in years. In line with the 100th birthday business, this seems like an appropriate time to retell it.

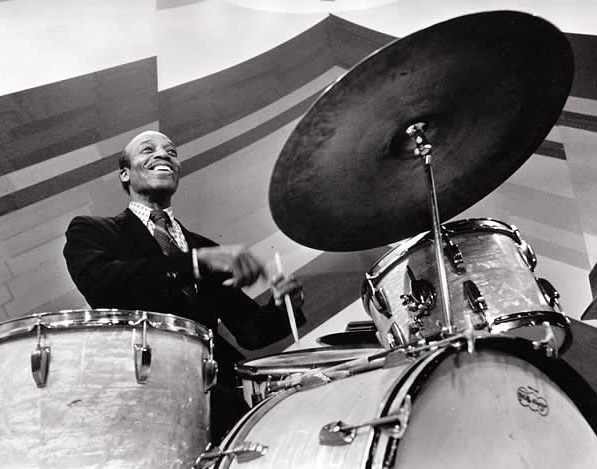

In the mid-1980s, I had the bright idea of writing a biography of Gene Krupa, which later became “World of Gene Krupa: That Legendary Drummin’ Man,” published in 1990 and still in print via Pathfinder Publishing of California. For an unpublished author writing about someone relatively forgotten back then, the project was an uphill battle from the start. Still, I forged ahead, and though a good deal of the book was a compilation of edited, previously published materials, I obviously had to get some first-person interviews to give the project some credibility. When I started, I had no publisher and not much of anything else, other than my credentials as a drummer and newspaper editor, but players like Teddy Wilson, Eddie Wasserman, Carmen Leggio, John Bunch, Charlie Ventura, and later, Mel Torme’ (who wrote a wonderful introduction to the book, where he revealed that Gene was, in fact, Goodman’s absolute, favorite drummer of all time) were just marvelous to me.

But it was always in the back of my mind that any book about Krupa just had to have an interview with one, Benjamin David Goodman.

My plan was this: Find the New York phone number and ask BG’s’ long-time secretary, who I believe was still Muriel Zuckerman, if there was a chance at setting up a future phone interview. Goodman’s office number was listed, and having heard all the stories about this strange guy through the years, and the fact that he remained one of my musical idols, I really had to get some serious courage going before I dialed the phone.

Zuckerman answered the telephone, and I did not misrepresent my credentials or the project’s status. “I’m writing a book about Gene Krupa,” I told her, “and I was just wondering…next to setting up an interview with God, how difficult would it be to set a time to do a five-minute phone interview with Mr. Goodman?”

Always the merry prankster, I thought injecting a bit of humor into the proceedings might help pave the way.

“You’d have a better chance with God,” Zuckerman replied, and then asked if she could put me on hold for a moment.

Several moments later, someone picked up a telephone extension and said, “Hello?”

The voice was instantly recognizable. It was “Him.” I was not prepared for this at all.

“Mr. Goodman, I’m writing a book about one of your friends and colleagues, Gene Krupa, and I was wondering if I could set up a time to talk to you over phone about him for a few minutes,” I related.

“Well…what kind of questions do you want to ask?” was BG’s reply.

Man, was I on the spot, as I had absolutely nothing prepared, but I thought I came up with something reasonably intelligent.

“I’ve always wanted to know something, Mr. Goodman,” I answered while stalling for time. “You played with Gene at the very beginning of his career, and you played with him at the very end. Maybe you could explain the difference in how he accompanied you through the years.”

I thought that was a great question, and I still do. I’ll remember Goodman’s comments until the day I die.

“He played pretty much the same,” he explained. “He was rather consistent. As you know, he started with me and then formed his own band, which was rather successful. When did you say he died?”

“He died in 1973,” I told him.

“How old was he when he died,” asked BG.

“He was 64 years old, Mr. Goodman.”

“My, that was rather young, wasn’t it? Goodbye.”

Click.

That’s my Benny Goodman story and it was printed, verbatim, in my Krupa book. Several Goodman fans were not happy about it.

When players like Teddy Wilson gave a sensitive and intelligent analysis about how Krupa functioned—and evolved—as an accompanist and a soloist through the years, Benjamin David Goodman could only relate that Krupa’s playing “was pretty much the same” over a 40-plus year span.

But as one wag –who heard all the stories and more through the years—once put it: “Yeah, but he sure could play that clarinet.”

Happy 100th and long live The King.